Gervais Williams, joint Fund Manager of the Premier Miton UK Smaller Companies Fund, takes a look back at the history of small caps and shares why he believes now is the time to revisit them.

For information purposes only. The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author at the time of writing and can change; they may not represent the views of Premier Miton and should not be taken as statements of fact, nor should they be relied upon for making investment decisions.

The Law of Large Numbers

The Law of Large Numbers explains how the real world constrains the expansion of bigness. Hence, whilst global stock markets are dominated by large caps, ultimately, they can’t just keep growing forever into the future. When we look back into the past for example, the large cap arena is filled with numerous stocks that have either shrunk back considerably or ceased to exist. So large caps comprise some stocks that are currently keeping up with the global stock markets, along with numerous others that are faltering. Importantly, stock market returns from large caps reflect a group of stocks whose aggregate growth is slowing, including a number that disappoint badly. Don’t get me wrong – large caps can perform strongly at times, but their long-term returns are normally outpaced by others on the stock market.

Weak large caps tend to get caught out most often during global recessions. As demand falls back and their sales decline, they just can’t make up the difference with enough extra sales elsewhere. Of course, numerous quoted small caps lose out too, but being more immature, many can make up for lost sales by expanding into markets vacated by the retrenching corporates.

When the economic cycle is weak, typically some large caps with sizable index weightings end up delivering shockingly poor returns, that depresses the overall return of the mainstream stock market indices through the business cycle as a whole. During recessions some quoted small caps suffer disappointments too, but alongside there are others whose share prices appreciate by many multiples, because they have expanded so well into the vacated markets. Hence, small cap returns tend to outpace those of large caps over the longer term. In stock market terms, this is known as the small cap effect.

Clearly, small caps don’t outperform continuously. After small caps have outperformed by a wide margin for example, sometimes large caps have a year or two of catch up. At other times, a specific large cap industry sector might have a period of outperformance. But ultimately, over the long term, the small cap effect is a near universal feature of all global stock markets.

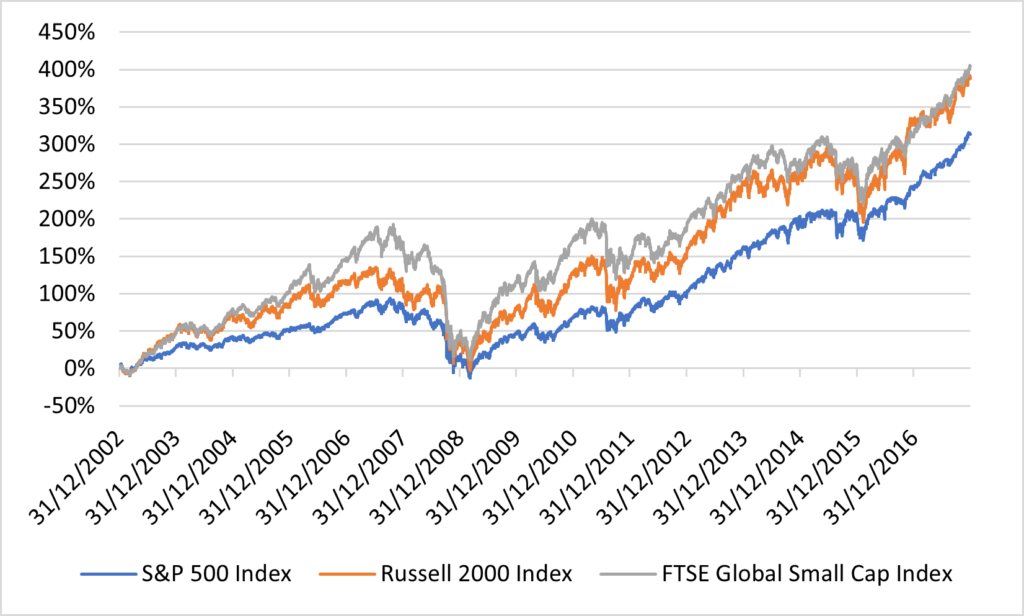

Since the FTSE Global Small Cap Index was first established in 2002, it and the Russell 2000 (an index of US small caps) have a history of outperforming the mainstream indices such as the S&P500 Index up to the end of 2017

Source: Bloomberg/Copyright 2024, S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC/FTSE Russell from 31/12/2002 to 29/12/2017

Past performance is not a guide to future returns.

Or at least that is…

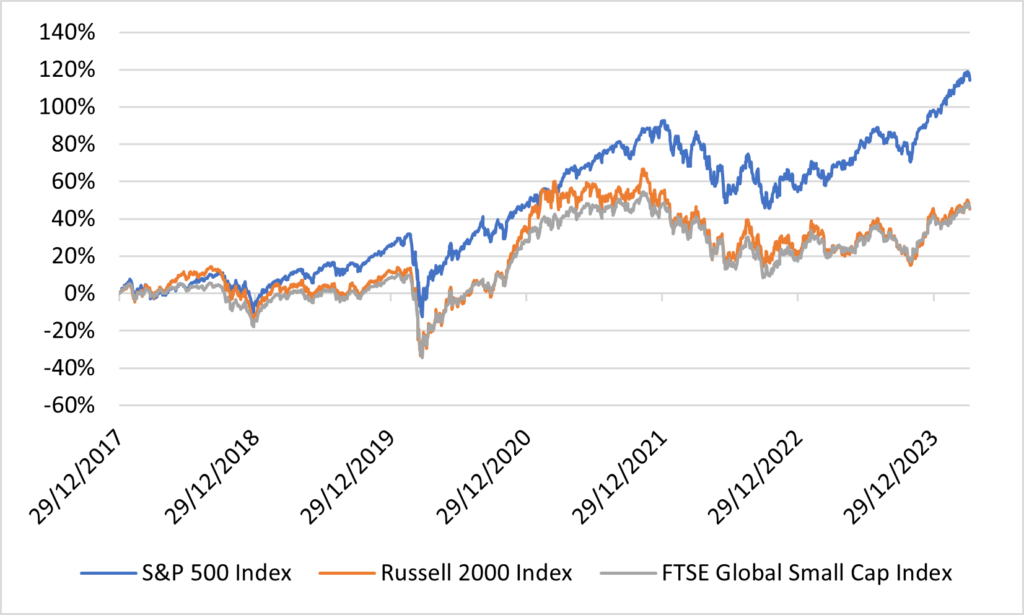

Since the end of 2018, the ‘smallcap effect’ appears to have gone into reverse, with the mainstream indices such as the S&P500 outperforming the FTSE Global Small Cap and Russell 2000 Indices

Source: Bloomberg/Copyright 2024, S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC/FTSE Russell from 31/12/2002 to 29/12/2017

Past performance is not a guide to future returns.

Or at least that is how it is normally… until 2018, when something changed. Whilst US small caps (as measured by the Russell 2000 Index) outperformed as normal up to six years ago, more recently they have underperformed dramatically. It’s a similar outcome for the FTSE Global SmallCap Index, which has subsequently performed just as poorly. What is going on?

Where does the answer lie?

The answer lies in the exceptionally strong returns delivered by many of the very largest quoted companies since 2018. In the US for example, large caps such as Microsoft, Apple, Tesla and others have delivered quite exceptional returns. In Europe, there has been a similar pattern with mega caps such as Novo Nordisk also outperforming very substantially.

Whilst many of these stock market leaders have delivered perfectly good earnings growth over recent years, in fact it’s an unusually large rise in their valuations that’s driven their exceptional returns. Alongside, whilst most small caps may have continued to trade well, in general their valuations have stagnated, and indeed in many cases have declined. This diverging pattern in stock market valuations is exceptional. Why are the valuations of large caps rising whilst the valuations of small caps losing out?

The use of Quantitative Easing

The seeds regarding this extreme valuation divergence lies in the Global Financial Crisis sixteen years ago when Quantitative Easing (QE) was first introduced. QE works by deliberately distorting asset valuations, so that they carry on rising through an economic setback. QE is great for an emergency such as the Global Financial Crisis. But subsequently, whenever economic growth wobbled even slightly, central banks have been quick to boost market valuations and inject additional demand via QE.

The key point is that over the last sixteen years, very few large caps have been caught out, so we have gradually become surrounded by a new type of company – zombies. Zombie companies are businesses that would normally have failed, but with QE have remained in business… albeit in suspended animation. In the absence of their failure, smaller, nimble companies never really get a proper chance to bring their vibrancy and innovation to a wider audience.

Since 2008, with the use and reuse of QE, market valuations have gradually risen and risen, so by 2018, asset valuations have been driven to simply absurd levels. Bond yields fell to zero – or below! And as the valuation of large cap equities rose and rose, they’ve been able to accelerate the issue of new high-price shares to boost their earnings growth. In short, over recent years some large caps have morphed into mega caps, and just like the dinosaurs they have come to dominate the landscape. Meanwhile, in the absence of corporate failure, even through the pandemic-induced recession, small caps just haven’t been able to expand into markets vacated by failing corporates.

QE is only viable as a policy when an ongoing surge of low-cost imports supresses inflation. But gradually over the years, the electorate have come to distrust the compromises that come with QE and globalisation. Therefore, as long ago as 2016, they have started to vote against globalisation – Brexit, Trump etc. Thereafter, the logistic nightmares of the pandemic have made the compromises that come with QE and globalisation headline news. Injecting giant QE when the ongoing surge of low-cost imports is bottlenecked, has brought inflation back to life.

Initially, central banks hoped that the inflationary surge was ‘transitionary’ and kept interest rates super-low. Subsequently, when they were obliged to raise interest rates substantially, the giant mega cap edifice wobbled badly. During 2022, asset valuations started to collapse, and various US banks started to fail. For now, the central banks have found ways to boost asset valuations by any means they can. Alongside, governments have injected extra demand by running up their budget deficits to war-time levels.

But the electorate are becoming ever more insistent in bringing globalisation to an end. In Europe, aggressively nationalistic parties are gathering an increasingly large proportion of the vote. Trump Mark II seems likely to be elected later this year – with a highly aggressive nationalistic agenda. Globalisation is now in headlong retreat, and hence any extra QE from here will merely drive-up inflation and accelerate the failure of zombie companies.

Ultimately of course, we always knew that the Law of Large Numbers would have its way. With mega cap valuations so high, the global stock market indices can only hope to flatline over the coming decade or two. We’ve finally reached a giant turning point.

Hang on to your hat!

The scene is set for an explosive period of small cap recovery. The Magnificent 7 (the seven largest US-quoted mega caps) alone are valued at 120-fold the market capitalisation of the whole of the FTSE AIM All Share Index. And then there are all the other global mega caps. Reallocating just 1% from mega caps to small caps dramatically scales up its impact, so the new small cap supercycle is currently on a hair trigger.

The key point is that quoted small caps have already had their bear market. They’re already standing on absurdly sub-normal valuations because capital flows over recent years have skewed so heavily into mega caps. As I say, the new small cap supercycle is on a hair trigger and with the electorate voting this year, the formal demise of globalisation is now imminent. The scene is set for an explosive period of small cap recovery. Hang on to your hat!

Gervais Williams

Fund Manager, Premier Miton UK Smaller Companies Fund